| Noticias |

Yoshoku

por Raphael

Sushi is Japan’s most famous food, but it would surprise most Westerners to learn that according to a 2005 survey of elementary and middle school students, sushi was tied for first place with a dish called “kare raisu,” or “curry rice,” a meal which is not domestic to Japan at all. Curry rice is just one dish among many that in the culinary category known as “yoshoku,” which literally means “Western food.” Restaurants that serve yoshoku are everywhere, and this hybrid Japanese-world cuisine draws its influences from all over the globe: curry from India, spaghetti from Italy, “Hamburg steak” which references both Germany and America, and many more. However, these foreign foods are usually not presented in a purely authentic manner, but are blended with local ingredients and techniques to suit Japanese tastes.

Yoshoku is not new to Japan, but has been developing for over a century and a half, since Japan re-opened its borders to the West. Japanese chefs have had to adapt the cuisine both to the Japanese palate, and to the ingredients that were available to them at the time. For example, it is common in yoshoku to season foods with ketchup rather than fresh tomatoes or marinara sauce. This is because, when certain yoshoku foods like “spaghetti Neapolitan” or “omu raisu” (a thin omelette wrapped around ketchup-seasoned rice) were invented, fresh tomatoes were rare in Japan. Although tomatoes are ample in Japan today, these yoshoku foods now have a tradition of their own. To reintroduce ingredients that might be more authentic would be to change the dishes that many Japanese people have come to love.

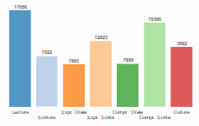

Data from surveys make the popularity of yoshoku obvious. One such survey suggests that Japanese people eat curry-rice eighty times a year on average, which is more than once a week, making Japan one of the world’s biggest curry-consuming nations. Besides curry-rice, omu-rice, steak, cake, pizza and (Italian-style) pasta all ranked among the top ten favorite foods for children under 15. In Kappabashi, where cookware shops line the streets, plastic models of food for use in the restaurant industry are available for purchase. Purchasing this realistic fake food for a souvenir became so popular amongst tourists that versions of omu-rice and other popular yoshoku dishes have been made into refrigerator magnets and cell phone straps. Yoshoku is clearly a big part of Japanese pop culture, but there was a time when Western food was alien and intimidating to Japanese people.

In traditional Japanese cuisine, fish and rice are the most important elements. Rice has long been considered the anchor of any Japanese meal, and anything else eaten during a Japanese meal is considered a side dish to complement the rice. As an island nation with long coastlines, Japan has always enjoyed a large supply of fish, which along with soy beans has been Japan’s most important protein source. In the seventh century, according to Buddhist precepts, Emperor Tenmu banned the killing of livestock for meat, making meat unpopular. Even when Europeans arrived in the 16th century, their guns caught on faster than their meaty cuisine, which did not appeal to most Japanese people. In the 17th century, the shogunate closed Japan to most foreigners, limiting contact with the West until 1853, when US Admiral Matthew Perry forced the country open to the West.

During that time, Japan rapidly began experimenting with the technology and culture of the West. Perry even brought Western food to offer the officials who made the end of isolationism official: wine, beef steaks, and mutton especially were revelations to these diplomats. As Japan’s government attempted to improve the physique of its citizens, they encouraged people to eat meat. At diplomatic functions, French food was often served, which was seen as an official endorsement of foreign food.

Still, many Japanese people were uncomfortable with eating meat. In Yokohama, a large port city where many foreigners lived, and the birthplace of a yoshoku beef stew known as “gyuu nabe,” mixing Japanese ingredients into Western foods helped the popularity of yoshoku along. Adding miso sauce to the gyuu nabe helped it become palatable to Japanese people. Another example is the veal cutlet: originally pan fried with butter in the French style, this meal did not appeal to early Japanese consumers of yoshoku, who were unfamiliar with butter. One chef hit on the idea of using the same deep-frying technique used for tempura, a native Japanese cuisine, to fry meat cutlets. The result, a fried pork cutlet known in Japan as “ton katsu,” remains extremely popular today. Many consider these yoshoku experiments an illustration of Japan’s tendency to accept imports from other countries, but to also adapt these imports and redefine them in a Japanese context.

Since the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 destroyed so much of Eastern Japan, the newly rebuilt cities included many more yoshoku restaurants, and the fashion for Westernization only increased. Although yoshoku was not often cooked at home during that time, after World War II, Occupation forces promoted eating yoshoku for health and strength. When this was coupled with the economic boom of the 1950s, which made Western appliances available, brought television cooking shows into the home, and increased leisure time as well as disposable income for Japanese people, yoshoku became very popular to cook at home.

Yoshoku versions of food are often very different from the originals on which they were based. Japanese curry, for instance, is rarely spicy and sometimes even sweetened with honey, apple, or yogurt. In Japanese spaghetti, noodles are often cut short so that they are easier to eat with chopsticks. Pizza often sports corn, mayonnaise, or shrimp as toppings. However, these days many more Japanese people have the opportunity to travel abroad, and Japanese cities are becoming more cosmopolitan and international all the time. Tasty, authentic, foreign food can be found in many places in Japan, but yoshoku is a separate cuisine entirely, the hybrid result of necessity and experimentation that can only be found in Japan.

Photo credits:

- http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%82%A4%E3%83%AB:Korokke.jpg

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hayashi_rice.jpg

| Aucun commentaire |